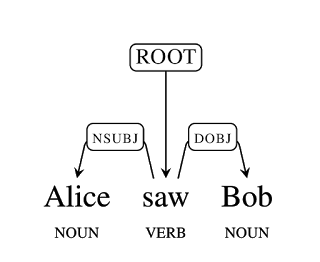

Source: Research Blog: Announcing SyntaxNet: The World’s Most Accurate Parser Goes Open Source

Month: May 2016

Fifty shades of open

Open source. Open access. Open society. Open knowledge. Open government. Even open food. The word “open” has been applied to a wide variety of words to create new terms, some of which make sense, and some not so much. This essay disambiguates the many meanings of the word “open” as it is used in a wide range of contexts.

Introduction

Open source. Open access. Open society. Open knowledge. Open government. Even open food. Until quite recently, the word “open” had a fairly constant meaning. The over-use of the word “open” has led to its meaning becoming increasingly ambiguous. This presents a critical problem for this important word, as ambiguity leads to misinterpretation.

“Open” has been applied to a wide variety of words to create new terms, some of which make sense, and some not so much. When we started writing this essay, we thought our working title was simply amusing. But the working title became the actual title, as we found that there are at least 50 different terms in which the word “open” is used, encompassing nearly as many different criteria for openness. In this essay we will attempt to make sense of this open season on the word “open.”

++++++++++

Opening the door on open

The word “open” is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a very old one in the English language, harking back to Early Old English. Unlike some words in English, the definition of “open” has changed very little in the intervening thousand-plus years: the earliest recorded uses of the word are completely consistent with its modern usage as an adjective, indicating a passage through or an access into something (Oxford English Dictionary, 2016).

This meaning leads to the development in the fifteenth century of the phrases “open house,” meaning an establishment in which all are welcome, and “open air,” meaning unenclosed outdoor spaces. One such unenclosed outdoor space that figured large in the fifteenth century, and continues to do so today, is the Commons (Hardin, 1968): land or other resources that are not privately owned, but are available for use to all members of a community. The word “open” in these phrases indicates that all have access to a shared resource. All are welcome to visit an open house, but not to move in; all are welcome to walk in the open air or graze their sheep on the Commons, but not to fence the Commons as part of their backyard. (And the moment at which Commons land ceases to be open is precisely the moment it is fenced by an owner, which is in fact what happened in Great Britain during the Enclosure movement of the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries.)

Running against the grain of this cultural movement to enclosure, the nineteenth century saw the circulating library become the norm — rather than libraries in which massive tomes were literally chained to desks. The interpretation of the word “open” to mean a shared resource to which all had access, fit neatly into the philosophy of the modern library movement of the nineteenth century. The phrases “open shelves” and “open stacks” emerged at this time, referring to resources that were directly available to library users, without necessarily requiring intervention by a librarian. Naturally, however, not all library resources were made openly available, nor are they even today. Furthermore, resources are made openly available with the understanding that, like Commons land, they must be shared: library resources have a due date.

The twentieth century saw an increase in the use of the word “open,” as well as a hint of the confusion that was to come about the interpretation of the word. The term “open society” was coined prior to World War I, to indicate a society tolerant of religious diversity. The “open skies” policy enables a nation to allow other nations’ commercial aviation to fly through its airspace — though, importantly, without giving up control of its airspace. The Open University was founded in the United Kingdom in 1969, to provide a university education to all, with no formal entry requirements. The meaning of the word “open” is quite different across these three terms — or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that these terms use different shadings of the word.

But it has been the twenty-first century that has seen the most dramatic increase in the number of terms that use “open.” The story of this explosion in the use of the word “open” begins, however, with a different word entirely: the word “free.”

++++++++++

Speech, beer, and puppies

In 1983, Richard Stallman announced the GNU Project (a recursive acronym meaning GNU’s Not Unix), a “complete Unix-compatible software system,” which he announced he would give away for free (Free Software Foundation, 2014a). In 1985 Stallman founded the Free Software Foundation (FSF) to support the developing free software movement that coalesced around the GNU project. As Stallman himself discovered, however, “free” is itself an ambiguous word, and so the FSF found it necessary to define what it means for software to be free. According to the Free Software Definition, four essential freedoms must exist for users of free software:

Freedom 0: The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose.

Freedom 1: The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish.

Freedom 2: The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor.

Freedom 3: The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others.

The Free Software Definition defines the “free” in free software as being about liberty, not price: it is consistent with the principles of free software to sell copies. What makes software “nonfree” (proprietary) is if it restricts any of the four essential freedoms, thereby exerting control over the user. As Stallman writes, “you should think of ‘free’ as in ‘free speech,’ not as in ‘free beer’.” (Free Software Foundation, 2014b).

Instructions for setting up the software on your deep learning machine

dl-setup – Instructions for setting up the software on your deep learning machine

Source: saiprashanths/dl-setup: Instructions for setting up the software on your deep learning machine

What happened when a professor built a chatbot to be his teaching assistant – The Washington Post

These students were shocked to find out they’d been chatting with a robot all semester.

To help with his class this spring, a Georgia Tech professor hired Jill Watson, a teaching assistant unlike any other in the world. Throughout the semester, she answered questions online for students, relieving the professor’s overworked teaching staff.

But, in fact, Jill Watson was an artificial intelligence bot.

Ashok Goel, a computer science professor, did not reveal Watson’s true identity to students until after they’d turned in their final exams.

Students were amazed. “I feel like I am part of history because of Jill and this class!” wrote one in the class’s online forum. “Just when I wanted to nominate Jill Watson as an outstanding TA in the CIOS survey!” said another.

Source: What happened when a professor built a chatbot to be his teaching assistant – The Washington Post

React Is The New jQuery — OutSystems Engineering — Medium

I love jQuery.

Its minimalism, quality and consistency allowed me do anything with a few lines of code (often just a single one).

It brought a clean syntax to an inconsistent language.

It offered an abstraction over incompatible browsers.

It was solid. It was freaking fast.

It made me feel like a powerful hacker.

And I loved that a 12 year old kid could teach people how to use it.

Its bright future was not obvious at the start. Around the time it was born, there were several other competing libraries: Dojo, Prototype, Mootools, YUI.

But jQuery kicked everyone’s ass.

Now 10 years have passed, and we need more power.

Source: React Is The New jQuery — OutSystems Engineering — Medium

Designing tiny tools to find a tumor – YouTube

Source: Designing tiny tools to find a tumor – YouTube

MIA Primer: Ryan Peckner / Seminar: Yaniv Erlich (2016)

Reliably transmitting data over noisy channels with linear codes

Messages transmitted over noisy channels are liable to be corrupted by errors, which may by corrected by including extra information at the cost of increased complexity of decoding. We’ll learn about the class of linear error-correcting codes, which make use of linear relations among codewords to correct errors efficiently and automatically. These codes provide a powerful mathematical framework for combinatorial experimental design, wherein large numbers of biological specimens are pooled according to the rules of a code and assayed in aggregate.

MIA Meeting – https://youtu.be/WoCyfCm_kGM?t=2680

Yaniv Erlich

Columbia University (Computer Science), New York Genome Center

Compressed Experiments

Molecular biology increasingly relies on large screens where enormous numbers of specimens are systematically assayed in the search for a particular, rare outcome. These screens include the systematic testing of small molecules for potential drugs and testing the association between genetic variation and a phenotype of interest. While these screens are “hypothesis-free,” they can be wasteful; pooling the specimens and then testing the pools is more efficient. We articulate in precise mathematical ways the type of structures useful in combinatorial pooling designs so as to eliminate waste, to provide light weight, flexible, and modular designs. We show that Reed-Solomon codes, and more generally linear codes, satisfy all of these mathematical properties. We further demonstrate the power of this technique with Reed-Solomon-based biological experiments. We provide general purpose tools for experimentalists to construct and carry out practical pooling designs with rigorous guarantees for large screens.

Source: MIA Primer: Ryan Peckner / Seminar: Yaniv Erlich (2016) – YouTube

PostgreSQL: PostgreSQL 9.6 Beta 1 Released

The PostgreSQL Global Development Group announces today that the first beta release of PostgreSQL 9.6 is available for download. This release contains previews of all of the features which will be available in the final release of version 9.6, although some details will change before then. Users are encouraged to begin testing their applications against this latest release.

Major Features of 9.6

Version 9.6 includes significant changes and exciting enhancements including:

- Parallel sequential scans, joins and aggregates

- Support for consistent, read-scaling clusters through multiple synchronous standbys and “remote_apply” synchronous commit.

- Full text search for phrases

- postgres_fdw can now execute sorts, joins, UPDATEs and DELETEs on the remote server

- Decreased autovacuum impact on big tables by avoiding “refreezing” old data.

In particular, parallel execution should bring a noticeable increase in performance to supported queries.

Source: PostgreSQL: PostgreSQL 9.6 Beta 1 Released

Cargo Cult Science

by RICHARD P. FEYNMAN

Some remarks on science, pseudoscience, and learning how to not fool yourself. Caltech’s 1974 commencement address.

During the Middle Ages there were all kinds of crazy ideas, such as that a piece of rhinoceros horn would increase potency. (Another crazy idea of the Middle Ages is these hats we have on today—which is too loose in my case.) Then a method was discovered for separating the ideas—which was to try one to see if it worked, and if it didn’t work, to eliminate it. This method became organized, of course, into science. And it developed very well, so that we are now in the scientific age. It is such a scientific age, in fact, that we have difficulty in understanding how witch doctors could ever have existed, when nothing that they proposed ever really worked—or very little of it did.

But even today I meet lots of people who sooner or later get me into a conversation about UFO’s, or astrology, or some form of mysticism, expanded consciousness, new types of awareness, ESP, and so forth. And I’ve concluded that it’s not a scientific world.

Most people believe so many wonderful things that I decided to investigate why they did. And what has been referred to as my curiosity for investigation has landed me in a difficulty where I found so much junk to talk about that I can’t do it in this talk. I’m overwhelmed. First I started out by investigating various ideas of mysticism, and mystic experiences. I went into isolation tanks (they’re dark and quiet and you float in Epsom salts) and got many hours of hallucinations, so I know something about that. Then I went to Esalen, which is a hotbed of this kind of thought (it’s a wonderful place; you should go visit there). Then I became overwhelmed. I didn’t realize how much there was.

Source: Cargo Cult Science

Electron 1.0 is here

For two years, Electron has lowered the barrier to developing desktop applications—making it possible for developers to build cross-platform apps using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Now we’re excited to share a major milestone for Electron and for the community behind it. The release of Electron 1.0 is now available from electron.atom.io.

New to Electron? Electron is an open source framework that can help you build apps for Mac, Windows, and Linux. See how:

Source: Electron 1.0 is here